JavaScript Engines Hidden Classes (and Why You Should Keep Them in Mind)

A previous version of this post was published by accident 10 days ago. I didn't correct this mistake because it had been sitting on my hard drive for too long. Since many people seemed to enjoy reading it, I finally took time to finish it. You are reading the "augmented" edition of this article, the one where I stick to my initial plan. If you read the earlier draft of this post, you can jump to the top of the part I added or see the diff between the two versions (opens new window).

Another version of this article exists in French: Quelques rouages d'un moteur JavaScript (opens new window). Si vous êtes francophone, je vous recommande plutôt la lecture de cette dernière. Elle est peut-être plus marrante.

When V8 lead engineer Lars Bak1 describes (opens new window) V8 design decisions, the first thing he talks about are hidden classes.

To better understand hidden classes we need to know what problem they solve. This article is a first introduction to this concept. It will:

- cover fast property access because it's something hidden classes make possible,

- explain what hidden classes are and where they come from,

- tell you how you can observe them in their natural habitat because Chromium provides us with an awesome microscope,

- show you why keeping them in mind can improve your JavaScript performance eg. by avoiding property deletion or bailouts.2

Properties in an OO World

In a class-based object-oriented language such as C++, Java or C# in which you cannot add or delete methods and properties from an object on the fly, accessing properties is generally not costly. You can store object properties at fixed memory offsets because the object layout for an instance of a given class will never change.4 In this case, accessing a property can often be done with a single instruction: load the thing located at the given memory offset.

In an imaginary Java virtual machine, a Java object could be stored in memory as a simple structure which is the exact same for all instances of a same class. The properties (attributes, methods, …) are either primitive Java types (int, float, …) or pointers (to arrays, functions, …). This structure doesn't hold the "whole" object data, it merely holds references (memory offsets) to where the "real" data is stored. Or as another JVM could do, an object could be stored as three simple pointers: the first one to the class object representing the type of the object, the second one to a table holding pointers to the object's methods, the third one to the memory allocated for the object data.

At this point, you noticed I'm mainly talking about strategies to store an object in memory and access their properties. We call this property access which means retrieving the value of an object property. It's a mechanism we use all the time, here is how we leverage it in JavaScript:

const o = { // object

f: (x) => parseInt(x, 13),

1337: 13.37 + 20

};

o.f // property access => function f

o[1337] // property access => 33.37

o.f(o[1337]) // performs two property accesses and one function call => 42

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

As you may know, JavaScript is prototype-based (and class-free, not class-based).

Objects are mutable in JavaScript, so we can augment the new instances, giving them new fields and methods. These can then act as prototypes for even newer objects. We don't need classes to make lots of similar objects.

Not only are objects created by "cloning" existing prototypes, they can also be created by using the literal notation (or initializer notation (opens new window)) which you then can just as easily modify on the fly.

An important part of running some JavaScript code is creating objects, putting them in memory and retrieving them or only retrieving some of their properties. We will focus here on ordinary JavaScript objects (opens new window) (as opposed to exotic objects (opens new window)) and discuss property access techniques.

The Property Access Problem: Dynamic Lookups are Slow

Let's get back to the topic: how can we implement property access? Looking at what the ECMAScript 2015 specification proposes is a good starting point.

Under section 9 Ordinary and Exotic Objects Behaviours (opens new window), 9.1.8 [[Get]] (opens new window) describes the following algorithm (simplified for the purpose of this article):

When we do obj[prop] or obj.prop, …

- Make sure

typeof propis either'string'or'symbol'. (obj[13]does in factobj['13']3.) - If

propis a direct property ofobjandobj[prop]is notundefined, returnobj[prop]. End. - If

propis not a direct property ofobjor ifobj[prop]isundefined, then a. Let parent beobj's prototype b. Do the same as2.using parent instead ofobj. c. If parent isnull, returnundefined. End. d. Go down the prototype chain: go back to1.but with parent instead ofobj(which means it'll retry the same procedure withparent[prop]).

This is called dynamic lookup. This lookup is dynamic because at runtime we try to find prop on obj, if we fail we try the same on its prototype, then on the prototype's prototype, etc.

We could implement a (big) dictionary (or associative array) where you would store all the objects used by the program. Keys would be references to objects and the values would in turn be dictionaries with their properties as key and values:

// Your JavaScript code:

function Point(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

const p1 = new Point(12, 3);

const p2 = new Point(5, 9);

const p3 = new Point(12);

const lit = { name: 'Bond' };

// The JavaScript engine's dictionary storing the objects

const allObjects = {

o0: { // p1

__proto__: 'p6a1251', // Object{constructor: Point(x, y), __proto__: Object{constructor: Object()}}

x: 12,

y: 3

},

o1: { // p2

__proto__: 'p6a1251', // Object{constructor: Point(x, y), __proto__: Object{constructor: Object()}}

x: 5,

y: 9

},

o2: { // p3

__proto__: 'p6a1251', // Object{constructor: Point(x, y), __proto__: Object{constructor: Object()}}

x: 12

},

o3: { // lit

__proto__: 'p419ecc', // Object{constructor: Object()}

name: 'Bond'

}

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

V8 is not implemented in JavaScript, but this should give you a basic idea of how we could store all the objects used in a JavaScript program using a dictionary. (This dictionary would probably be implemented as a hash table.)

Now let's say we want to get p1.z, p1 being the first object created in our program hence having o0 as reference. Let's roughly follow the algorithm we took from the ECMAScript spec:

- Find

o0inallObjects(lookup to resolve the object's location in memory), - Find a property named

"z"ino0(dynamic lookup to resolve the property's location in memory) and return its value. (Should we have triedp1.x, we could have stopped here, returning12.) - Since

o0does not have a property named"z", fetcho0.__proto__to see if it has a property named"z", otherwise look ifo0.__proto__.__proto__has a property named"z", repeat this process down the prototype chain (opens new window) until__proto__(opens new window) isnull(which means no object prototype was found).

As you can probably guess, this process is not efficient.

The Property Access Solution: Hidden classes

Instead of resorting to dynamic lookup to access properties, V8 implements hidden classes, a concept originally present in another prototype-based programming language: SELF. Here is a quote from the abstract of the 1989 paper which first described this idea: (emphasis is mine)

[…] SELF implementation runs twice as fast as the fastest Smalltalk implementation, despite SELF's lack of classes and explicit variables.

To compensate for the absence of classes, our system uses implementation-level maps to transparently group objects cloned from the same prototype […]

Hidden class is a better, more explicit name for what this paper calls a map. It makes reference to SELF and avoids confusion with the Map data structures and their JavaScript implementation Map Objects (opens new window), although in fact they really are named maps in V8. This short vocabulary brief will prove handy when we'll start digging into V8. I'll mostly stick to the hidden classes terminology but don't be surprised if I drop a map here and there for variety.

Most of the modern JavaScript engines we use today implement similar approaches or hidden classes variants. Safari JavaScriptCore (opens new window) has structures. Microsoft Edge's ChakraCore has type (opens new window)s. Firefox' SpiderMonkey has shapes:

There are a number of data structures within SpiderMonkey dedicated to making object property accesses fast. The most important of these are Shapes. […] Shapes are linked into linear sequences called “shape lineages”, which describe object layouts. Some shape lineages are shared and live in “property trees”. Other shape lineages are unshared and belong to a single JS object; these are “in dictionary mode”.

Everyone seems to use variants of these hidden classes but what do they look like, how are they generated? Let's take a look at what V8 does. Here is our Point function again:

function Point(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

const p1 = new Point(13, 37);

const p2 = new Point(2);

const p3 = new Point();

const p4 = new Point(4, 2);

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

From what we read about hidden classes (or maps) we could expect our engine to create a map for Point as soon as it assigns p1 and reuse this same map for p2, p3 and p4. Not quite. We are in fact looking at 3 related but different maps here. (Although this part is well illustrated in V8 design reference (opens new window), their documentation hasn't been updated for almost 4 years and it's worth paraphrasing.)

Let's start with the first part of our code. We define a function Point which we'll use as constructor for many points. It has two parameters, x and y, and its objects will remember the arguments we pass to this Point constructor.

function Point(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

2

3

4

At this point in time V8 puts our function in memory but we don't really care about this, our point is what happens when we create a point:

const p1 = new Point(13, 37);

When V8 sees our first usage of the Point function (or constructor) to create a new object based on this Point prototype it doesn't yet know what a Point really looks like, all it knows is function Point so it creates an initial version C0 of the hidden class p1 needs.

This first hidden class C0 represents a Point object without any property ({}). At the same time, V8 allocates our p1 variable as some memory object containing nothing but a class pointer to store the fact that p1's hidden class will be C0 for now.

Entering the Point function with our arguments 13 and 37, the next thing V8 encounters is this.x = x;, which resolves to this.x = 13;. Aha! The point p1 (which is this here) has a property called x and this property is not part of the map C0! First thing first, 13 is put in memory at this object's first memory offset (the spots where all the data contained in an object is stored) - we'll call it offset 0. V8 then creates a new hidden class C1 based on C0. What C1 brings to the table is a reference to a property named x, for which the data is stored at the object's offset 0.

V8 modifies C0 to tell it that each time an object with the hidden class C0 gets a property named x added to it, this object will have to transition to using C1 instead as its hidden class.

Next line is this.y = y;, ie. this.y = 37. Here is what happens internally: First 37 is stored at the next memory offset, offset 1. Then a new hidden class C2 is created by cloning C1 (I say cloning because C2 is the same as C1 at this point: it has a reference to a property named x for which the data is at offset 0). C2 receives the additional ability to have a property named y, for which the data can be found at its object's offset 1.

Now that we have a more capable hidden class than C1, C1's transition plan is updated to tell all C1 objects that they can transition to using C2 should they get a property named y set to them.

Let's get back to our example one last time:

const p1 = new Point(13, 37);

const p2 = new Point(2);

const p3 = new Point();

const p4 = new Point(4, 2);

2

3

4

I said that we had 3 hidden classes here, and I showed through which hidden classes p1 transitioned before being finally assigned C2. As you might probably guess, these for Points will end up with the following hidden classes:

/* C2 */ const p1 = new Point(13, 37);

/* C1 */ const p2 = new Point(2);

/* C0 */ const p3 = new Point();

/* C2 */ const p4 = new Point(4, 2);

2

3

4

To make sure you understood this concept of hidden classes and transition plans, here is a small exercise for you. Still using the small Point definition, try imagining what it will look like:

const p5 = new Point(13, 37);

p5.a = 'a';

const p6 = new Point(13, 37);

p6.b = 'b';

2

3

4

Here's the solution:

Since a transition is only created when we add a property to an object, the transition plan is a DAG (opens new window). It's a directed (we have arrows going from a vertex to another one) acyclic (it's not possible to start at a vertex and go back to it by following the directed edges) graph (the vertices are hidden classes).

In practice

What happens if we delete a property of an object?

const p = new Point(1, 2);

delete p.y;

p.y = 10;

2

3

Imagine if deleting a property was creating a transition saying "if the property y of an object which hidden class is C2 doesn't exist, this object is transitioned to the hidden class C5."

We would then have an object which hidden class is C5, and what would happen if we added a property y to this object? It would need to be transitioned back to C2! And to reach this conclusion, V8 would need to check if a hidden map exists for this specific case, and find it if it does. It would be a bit costly. In the transition plan we would have C2 without y -> C5, C5 with y -> C2. A cycle. That complicates things.

Remember I told you transitions between hidden classes were a DAG, so a graph in which you have no cycles? So what really happens when we delete a property? V8 simply decides that the object from which we deleted properties won't be backed by a hidden class. Accessing its properties won't be fast. Such objects are said to be in dictionary mode. It'll be treated as a dictionary - a hash map - a bit similarly to the "naive" property access implementation explained at the beginning of this article.

This might all seem a bit schematic and by now you are probably wondering if you could observe this behaviour all by yourself. Fortunately, Chrome developer tools allows us to do just that. Kudos to their team for exposing hidden classes to the end users. Someone at Mozilla told me they considered adding this capability to their own developer tools but nobody implemented it… yet.

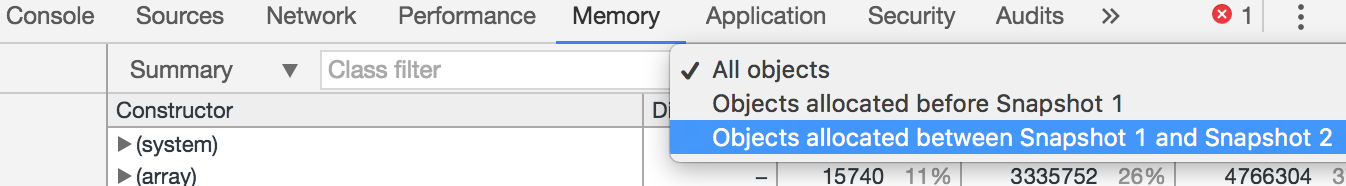

If you want to play along, open a tab (preferably blank, for example about://blank) in Google Chrome or Chromium, fire up the devtools, open the devtools settings (focus the devtools and hit F1) and enable Show advanced heap snapshot properties in the Profiler section of the Preferences tab. Go to the "Memory" tab (note: older Chrome version have this tab named "Profiles") and take a heap snapshot. Then run the following code in the "Console" tab and take another heap snapshot afterward. Last step: filter the objects list to only display the ones allocated between your first and your second snapshot:

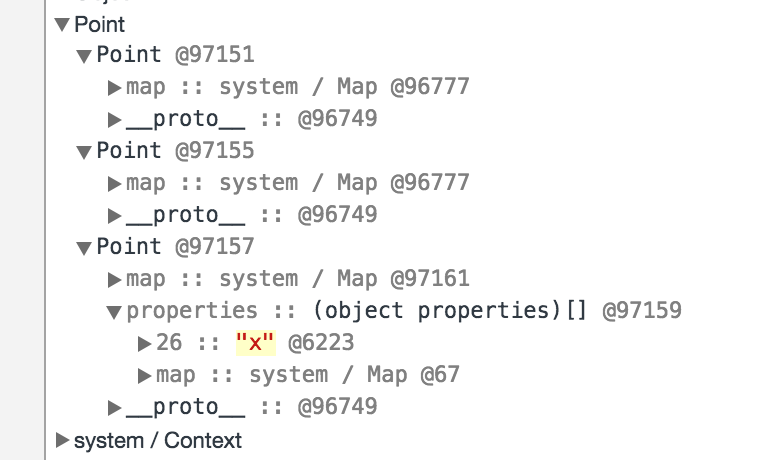

Below is a screenshot of Chrome devtools showing the state of the three following objects:

function Point(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

const p1 = new Point(1, 2);

const p2 = new Point(2, 3);

const p3 = new Point(3, 4);

delete p3.y;

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Here we see that the objects p1 and p2 share the same Map, the internal reference of which being 96777. By contrast the third object, p3, has a property hashmap : it is therefore in dictionary mode.

Hidden Classes Benchmarked

I summarized a few key points of this blogpost in the following benchmark:

'use strict';

var _shuffle = require('lodash/shuffle');

var Benchmark = require('benchmark');

function Point(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

var obj1 = new Point(1, 2);

var obj2 = new Point(2.1, 3.1);

var obj3 = new Point(3, 4);

delete obj3.y;

console.log('obj1 has fast properties:', %HasFastProperties(obj1));

console.log('obj2 has fast properties:', %HasFastProperties(obj2));

console.log('obj3 has fast properties:', %HasFastProperties(obj3));

var len = 1000;

var access = _shuffle('xy'.repeat(500).split(''));

var suite = new Benchmark.Suite();

// case 1

suite.add('obj1', function() {

var xs = [];

for(var i = 0; i < len; i++){

xs.push(obj1[access[i]]);

}

})

// case 2

.add('obj2', function() {

var xs = [];

for(var i = 0; i < len; i++){

xs.push(obj2[access[i]]);

}

})

// case 3

.add('obj3', function() {

var xs = [];

for(var i = 0; i < len; i++){

xs.push(obj3[access[i]]);

}

})

// case 1b

.add('obj1b', function() {

var xs = [];

for(var i = 0; i < len; i++){

xs.push(obj1[access[i]]);

}

eval();

})

// case 2b

.add('obj2b', function() {

var xs = [];

for(var i = 0; i < len; i++){

xs.push(obj2[access[i]]);

}

eval();

})

// case 3b

.add('obj3b', function() {

var xs = [];

for(var i = 0; i < len; i++){

xs.push(obj3[access[i]]);

}

eval();

})

.on('cycle', function(event) {

console.log(String(event.target));

})

.run({ 'async': false });

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

Please note:

- Before

delete,obj1,obj2andobj3share the same hidden class. %HasFastPropertiesis a V8 "native" function. To use V8 native syntax, you need to pass the following flag to node or Chrome:--allow-natives-syntax.- Cases

1,2and3will go through the optimizing compiler. - Cases

1b,2band3bwon't go through the optimizing compiler. It will bailout when noticing "eval" and noticing it doesn't know how to optimize functions containingevalit won't even try. The bailout reason (opens new window) will be Function calls eval. - (Executing this benchmark requires these two dependencies:

npm install benchmark lodash.)

Results :

$ node --allow-natives-syntax access-props.js

obj1 has fast properties: true

obj2 has fast properties: true

obj3 has fast properties: false

obj1 x 52,314 ops/sec ±0.82% (91 runs sampled)

obj2 x 53,153 ops/sec ±1.02% (85 runs sampled)

obj3 x 16,956 ops/sec ±0.89% (90 runs sampled)

obj1b x 22,948 ops/sec ±0.78% (89 runs sampled)

obj2b x 23,495 ops/sec ±1.09% (89 runs sampled)

obj3b x 10,632 ops/sec ±1.03% (89 runs sampled)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Here are a few observations:

p3doesn't benefit fromfast property accessbecause we deleted one of its properties. The function it which we accessp3's properties a bunch of times became 3.3x slower.- The bailout caused by

evalin the 3 last cases made them run 2.3x slower. ~2x slower isn't a huge difference, but keep in mind these functions are really trivial. They don't do much, there's not much to optimize in them. In some other cases, a bailout might well make a function run 10 or 20x slower.

Tiny conclusion

- Avoid

deleteing properties. - To avoid filling the heap with thousands of hidden classes, always initialize all possible properties of an object: it's more efficient to set some properties to

nulluntil you have a value to put in there than dynamically adding properties. - If you really have to add properties to objects, try doing it in the same order every time. For instance if you have an object

alphabet, and you first adda, thenb, thenc, when you have to add properties to anotheralphabetobject addathenbthenc. They will have the same hidden classes and the same transitions. Adding the properties in different order every time will create a bunch of useless hidden classes.

1 Lars Bak spent the last 30 years implementing and optimizing virtual machines. He worked on the SELF, Strongtalk, HotSpot, V8 and now Dart VMs. The best parts of V8 come from his previous experience. From SELF (which is similar to JavaScript in that they're both prototype-based OO languages) came inline caching, inlining and deoptimization. What was learned from Strongtalk became a big part of HotSpot's success. Which then heavily influenced V8 (JIT), and then Dart came inspired by Smalltalk, JavaScript, C# and Erlang while its VM only kept the best parts of SELF, Strongtalk and HotSpot. Notice the name HotSpot? It comes from its ability to profile bytecode at runtime and target "hot spots" (frequently executed parts of code, eg. hot functions or hot code) for optimization, just like V8 does (opens new window). ↩

2 This was my initial plan. I got lost on my way. The draft of this blog post has been sitting on my hard drive since February. I might publish a follow-up someday. 😃 ↩

3 If you didn't know that xs[0] is in fact xs['0'], you were probably under the impression that JavaScript has a "true" concept of Arrays. It's not the case, and it's wonderfully explained by James Mickens in this talk: https://vimeo.com/111122950 (opens new window). If you're in a hurry, jump to the minute 5:50 and watch until 12:20. But please don't, the whole thing is pure gold. ↩

4 edited 2016/11/30: I incorrectly compared Java and Smalltalk. In Smalltalk, it is possible to add methods or properties to objects instantiated from a class, as pointed out by MoTTs_ (opens new window). Their comment introduces a very relevant distinction between compile-time classes and inheritance and runtime classes and inheritance. ↩